Photo credit: r. r. jones

The Twin Passions of Kent Nagano:

Music and Community

By John Newman

The muted chaos of low voices quiets as the houselights come down. A shimmer of high strings forms in the dimness, a faint luminous veil over the audience, gathered on a Saturday afternoon last September in Los Angeles's Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. The passage is charged with promise and risk - the opening of the overture to Richard Wagner's Lohengrin.

Wagner's operas are the kind of musical and theatrical challenge that can be a crucible for any company. It is an audacious choice for the Los Angeles Opera. The company has made only two attempts at Wagner before, only one of which was well received, although it is widely known that the opera has ambitious plans to stage the composer's Ring cycle in 2003, complete with Hollywood special effects supplied by Industrial Light and Magic.

But the opera has recently undergone a change in leadership with Placido Domingo assuming the position of artistic director and Kent Nagano the post of principal conductor. It would be an exaggeration to say the future of the company rests on this single performance of Lohengrin, but there is a lot on the line. Now the rehearsals are over, the stage is set, and the afternoon is in the hands of the performers and Maestro Nagano, making his debut.

Not that anyone, including Nagano, has anything but confidence in his baton. Nagano, a 1974 graduate of UCSC (Porter College), is one of the most sought-after conductors in world. He is the music director of Berlin's Deutsche Symphonie and previously served in the same capacity for England's Hallé Orchestra and the Opéra National de Lyon in France. Nagano's energy, exacting artistry, and fresh ideas have invigorated every organization with which he's been associated. In fact, Nagano is so in demand as a conductor he's had to turn down a number of prestigious organizations seeking his services, including - initially - the Los Angeles Opera.

When Domingo first approached him about accepting the post of musical director, Nagano - though honored - felt that he needed to decline. "In Lyon, I enjoyed an extraordinarily effective partnership with a particularly great and visionary general director," Nagano says. "The freedom that we had to shape the identity of the opera house and establish its integrity was extraordinary and ideal. Because of this we were able to accomplish much more than was thought possible. It's rare to find that kind of partnership, and I hesitated to work in a house again unless it was under similar conditions."

What changed Nagano's mind was Domingo's vision of a uniquely West Coast opera house. "He asked me to help him create an opera house that has such a unique character that it could only be found on the West Coast of the United States. That was the deciding factor for me - the challenge to build an opera house that is not only of a very high standard, but which is unique to California culture, reflecting both the region's intersection with the great European tradition and its role as a major carrefour of the world."

As a native Californian, Nagano is well qualified to bring the perspective of the Golden State to the international opera community. He was born in Berkeley in 1951 (while his parents were both graduate students at UC Berkeley); but before he was a year old, his family relocated to the small Central Coast town of Morro Bay.

In those days, Morro Bay was a tiny coastal village with a farming and fishing economy. Though breathtakingly beautiful and idyllic, Nagano says, Morro Bay offered a music education that was unremarkable except in one very significant respect - affiliated with the public elementary school was a kind of music conservatory, established by an emigré from Soviet Georgia who had been trained in Munich Hochschule and was committed to the European musical tradition.

"We had to be there before 7 in the morning for private instruction," recalls Nagano, who played piano and clarinet. "We took instruction until school started, and after school we returned to the conservatory for orchestra and band practice. Between regular classes, music instruction, practice, and performance, the students who chose to study there very often ended up with 12-hour days."

The long hours of study produced a remarkable number of professional musicians, especially from such a small town. In addition to Nagano, for example, the local conservatory nurtured Jerry Folsom, who was later to become the principal horn for the Los Angeles Philharmonic. "I remember sitting a few chairs away from him in orchestra, and our families were friends," Nagano says. "I'm fairly confident that without those early years of education in the European discipline and traditions of art, aesthetics, and music, it would have been nearly impossible to even entertain the idea of a career in music."

In fact, when he first arrived at UC Santa Cruz in the fall of 1969, Nagano didn't entertain the idea. The early '70s were a period of social upheaval all over the U.S. and especially on college campuses. Like a lot of 17-year-old freshmen, Nagano hadn't decided on a career path, although he was investigating a number of possibilities including social sciences, politics, or - reflecting his rural upbringing - veterinary medicine.

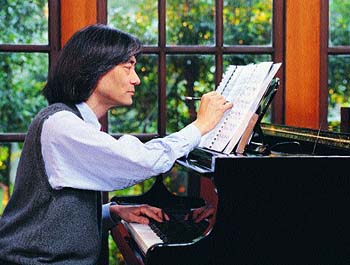

Maestro Nagano rehearses a Schoenberg piano concerto with

the Berkeley Symphony and pianist Mari Kodama.

"I had a keen interest in sociopolitical sciences, particularly international relations - an interest that remains today. It was a study that seemed very relevant at the time, and I had thought it might eventually lead to a profession of some international nature - perhaps the diplomatic corps, politics, or the legal field," Nagano says. "Though it did not occur to me at the time, these studies would prove to be an introduction to a life's work in international communication - one without words but through music, aesthetics, art, and theater, rather than politics."

Even though music wasn't his primary motivation for choosing UCSC, it played an important part in defining his interest in the campus. "UCSC had an unusually prestigious group of professors who headed the Music Department, some of whom I had already been exposed to through their writings. One particularly influential music teacher with whom I very much wanted to work with was Dr. Grosvenor Cooper. He and Dr. Edward Houghton [current arts dean at UCSC] had a tremendous effect upon the development of my interests."

Doing undergraduate study at UCSC had other benefits as well, and Nagano took full advantage of them. "The standard of the faculty was extraordinarily high, and, if you had the discipline and the interest, you could pursue a subject far beyond the time limitations of normal course work. My memories are full of hours, days, weeks, and months of extra seminars and private tutoring in Dr. Cooper's home, studying composition, counterpoint, and analysis - generous, private instruction, which continued for several years beyond graduation."

Even after he'd graduated from UCSC with dual degrees in sociology and music, Nagano still didn't think of music as a career. But during his last two years on campus, he found himself being asked with increasing frequency to conduct various ensembles or serve as assistant conductor for classes. "As passionate as my love for music was, conducting wasn't something I necessarily wished to pursue as a vocation. Rather, it was something I initially began more because there was a need."

For Nagano, though, his career path remained undefined. At the same time he enrolled at San Francisco State University for graduate work in music, he received permission to attend classes at the University of San Francisco in graduate-level sociology courses. "But one day I found myself doing more conducting than anything else - and it was at that point, I realized with some amazement that, at least technically speaking, I had become a conductor."

And he has been a very busy one ever since. In 1984, Nagano created a sensation by successfully conducting the Boston Symphony in a performance of Mahler's Symphony No. 9 with one day's notice, without rehearsal, and without ever having conducted the work before.

In spite of his international acclaim, Nagano has remained loyal to his West Coast roots. He is still music director of the Berkeley Symphony, for example, a position he has held for 23 years.

Photo credit: r. r. jones

Before he accepted the position with the Los Angeles Opera last fall, Nagano relinquished his positions as music director of the Hallé Orchestra (after a tenure of nine years) and the Opéra National de Lyon (under his guidance for almost 10 years). Under his leadership, both companies rose to prominence and established an international reputation for innovative productions of exceptional quality.

Nagano is also one of the most prolific conductors ever to step into a recording studio, and his recordings have received international acclaim. A multiple Grammy winner with four of his recordings having won the prestigious award, Nagano has also received international honors from England, Germany, France, and Belgium. The first recordings he made with the Lyon company, French versions of Strauss's Salome and Prokofiev's Love for Three Oranges, were instant sensations. Mark Swed, music critic for the Los Angeles Times, declared Nagano's recordings of Busoni's Doktor Faust (with the Lyon company), Messiaen's Saint François d'Assise (from the Salzburg Music Festival), Peter Eötvös's opera Three Sisters (which Nagano commissioned and premiered in Lyon in 1988), and Leonard Bernstein's A White House Cantata (the concert version of the musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, which Nagano premiered in London in 1999) "the four most necessary operatic recordings of the century's end."

Nagano's elegant operatic refinements haven't necessarily been restricted to the orchestra pit, either. In Lyon he brought in celebrated Japanese architect Arata Isozaki to design sets for the company's first production of Madam Butterfly and legendary Japanese film director Hiroshi Teshigahara to direct its first production of Turandot. Los Angeles can expect a similarly inventive approach.

In addition to his current post at the L.A. Opera, Nagano continues to serve as music director of Berlin's Deutsche Symphonie and is active as a guest conductor with many of the world's foremost orchestras and opera companies. In spite of his international acclaim, he has remained loyal to his West Coast roots. He is still music director of the Berkeley Symphony, for example, a position he has held for 23 years.

It was with the Berkeley Symphony, in fact, that Nagano began building his reputation for serious and ambitious projects, such as a survey of Messiaen's epic orchestral works in the early 1980s. While preparing a series of performances of Messiaen's work, Nagano developed a relationship with the French composer that eventually led to Messiaen's arrival in Berkeley for a performance of his work The Transfiguration of Our Lord Jesus Christ, as well as Nagano's participation in the 1983 world premiere in Paris of Messiaen's opera Saint François d'Assise.

As a part of his vast symphonic repertoire, Nagano makes it a priority to bring quality productions of modern composers to the public. At the Salzburg Festival in 2000, he conducted the world premiere of Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho's opera L'Amour de loin. At the Berlin Festival that year, he conducted the Deutsche Symphonie in an evening of works by Stockhausen, along with his Bruckner cycle. At the end of the year, he premiered a new nativity oratorio for the millennium, El Niño, by John Adams, in Paris. A longtime friend and advocate of Adams, Nagano also conducted the premiere of Adams's most controversial work, The Death of Klinghoffer, in Brussels, and later conducted an award-winning recording of the work.

"It is a special and tremendous responsibility to create or present a piece that has never been heard," Nagano says. "The audience relies upon your judgment and needs to trust you to introduce them to works which are just as provocative and performed with the same high standard of quality that we have in traditional literature. If you don't compromise quality of repertoire or performance, the public will follow you. Through this commitment, the opera house becomes a vital and integral part of the community."

"These studies would prove to be an introduction to a life's work in international communication - one without words but through music, aesthetics, art, and theater, rather than politics."

Photo credit: r. r. jones

Nagano is aware that making the Los Angeles Opera a living part of that vast multicultural community will be an enormous challenge. "Los Angeles is assuming an ever-increasing role as one of the most important centers of the whole world," he notes, "midway between Europe and the Pacific Rim, and influenced by the traditions of both. Mr. Domingo and I both feel that this is an opportunity for the Los Angeles Opera to reflect some of the tremendous diversity of the area on the stage with the performers, in the repertoire that's chosen, and in the commission of new works by composers like Luciano Berio and Unsuk Chin. We also want to bring in important traditional works that haven't been performed in Los Angeles, such as Lohengrin and The Ring cycle."

That Nagano is taking on such a challenge is no surprise to anyone familiar with his long-standing commitment to both music and the social sciences. "Cultural institutions are meant to serve, lead, and reflect the community," he says. "If and when they don't, they are at immediate risk of becoming irrelevant. Should they become irrelevant, they surely will not survive. This is particularly true in opera because the art form is so expensive."

So far, Nagano's formula for social relevance has proven to be a recipe for success in Los Angeles. By the time the lights came up on the Saxons and the Brabants, in the opening scene of Lohengrin in last September's performance, everyone in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion knew that the hands of the maestro had fashioned yet another success - and, in the process, were brightening the future for opera fans on the West Coast.

UCSC Chancellor M.R.C. Greenwood, Placido Domingo, and Kent Nagano at the reception following the debut of the L.A. Opera's performance of Wagner's Lohengrin

Photo credit: Kim Canazzi

After 9/11: Nurturing Hope Through Music

Where were you when you heard the news on September 11? Kent Nagano, like a lot of other people, was on his way to work, but in his case that meant on a plane enroute from Germany to Los Angeles to conduct the opening of Lohengrin at the Los Angeles Opera four days later. He knew something was wrong even before he got the news.

"We were about an hour and a half from L.A.," he recalls, "somewhere over Calgary, Canada, and the plane suddenly turned 180 degrees. After about an hour of flying in the wrong direction, and seeing the Rocky Mountains, which had just disappeared, reappear again, the captain came on the intercom and told us we had been ordered to go back to Germany. But he didn't tell us why."

It wasn't until the plane landed in Iceland to refuel that Nagano and his fellow passengers learned about the events at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. The flight returned to Frankfurt but wasn't allowed to land there and was diverted to another German city, Leipzig.

Nagano still needed to get to Los Angeles. After a few hours in Leipzig, he managed to get a flight to Munich. After a day in Munich, the opera company devised a circuitous route to get him to Los Angeles: From Munich he flew to Frankfurt, and from Frankfurt to Mexico City; from Mexico City, he caught a puddle jumper to Guadalajara, and then on to the border town of Tijuana, where a car was waiting to drive him to L.A. To make the trip complete, a bomb scare at the border crossing held him up for two more hours.

Nagano finally made it to Los Angeles, but one indirect consequence of the terrible events of September 11 was that the orchestra had to forgo its final rehearsals. In spite of that - and perhaps inspired by their need to contribute to the community in whatever way they could - the members of the company gave a tremendous performance. For many in the audience that afternoon, the message of hope and triumph of the human spirit in Lohengrin was a soothing balm for the soul.

"It really was a transforming experience," noted Chancellor M.R.C. Greenwood at a special postperformance reception the UCSC Alumni Association hosted that day to honor Nagano. "For a few hours, the beauty of the music, the artistry of the conductor, and the talent of the cast took us to another place and reminded us of the extraordinary change in our lives that music and art can make."

In addition to Nagano and the chancellor, speakers at the reception included artistic director Placido Domingo and UCSC arts dean Edward Houghton, who was one of Nagano's UCSC teachers and remains a collaborator, having researched and translated a Renaissance mass for a performance that Nagano conducted in fall 2000 in Berlin.

No matter the venue, though, Nagano-led performances seem to generate a rare kind of excitement. Just ask the nearly 100 guests at the UCSC alumni reception in Los Angeles.

- John Newman and Ann Gibb