What's Killing Panama's

Coconut Palms?:

UCSC sleuths hot on the trail of a mysterious disease

Photo: r. r. jones; coconut palm mola (detail)

courtesy of Gregory Gilbert

THE DEAD AND THE DYING: An epidemic of Porroca takes its toll on Kuna Yala's valuable coconut palms. Photo: Gregory Gilbert |

Graceful coconut palms are a fixture of the tropical landscape from Hawaii to Puerto Rico. Along Panama's scenic Caribbean coast, the statuesque trees dot the shoreline like pearls on a necklace.

The Kuna Yala region of Panama, made up of a 400-kilometer stretch of sandy beaches and 300 nearby islands, remains largely undiscovered by tourists. A semi-independent republic established in 1925, Kuna Yala is home to the Kuna Indians, an indigenous group whose subsistence lifestyle remains largely unchanged from the ways of their ancestors, who first inhabited the area in the 1600s. Each morning, islanders paddle dugout canoes short distances to the mainland to collect freshwater, harvest coconuts, and work small farm plots. Women in colorful blouses adorned with their hand-appliquéd needlework sit before thatch-roofed huts, tending children and preparing coconut-based dishes over open fires.

But in 1994, a mysterious disease began ravaging Panama's coconut palms, stunting new growth, stiffening leaves, and quickly killing many of the towering 60-foot trees. Unlike in Florida, where an outbreak of disease in the 1980s threatened the state's famous palm trees and triggered a well-funded and organized response from horticultural researchers, there was no outcry as this new disease took hold in Panama, jeopardizing the diet and economy of the Kuna.

Instead, a pair of adventurous young UC Santa Cruz plant scientists took up the challenge on their own time, slowly gaining the trust of the Kuna as they tracked the disease for several years. As the urgency of their undertaking grew, these dedicated researchers had to overcome the shortcomings of their training and follow the path of environmental science today--where ecological crises demand top-notch scientific skills and knowledge of anthropology, economics, political science, and sociology. As in many epidemics, answers remain elusive. But the researchers have compiled an arsenal of data that will prove invaluable in their battle to assist this little-known indigenous community.

Gregory Gilbert was a plant pathologist doing postdoctoral research with the Smithsonian Tropical Institute in Panama in 1994 when agronomists in Panama's Department of Agriculture made a troubling observation: Coconut palms in the Panama Canal region were getting sick and dying. Their new leaves were coming in dwarfed and deformed, then dying, leaving "headless" trunks that looked like the skeletal remains of the dead. Gilbert and his government colleagues immediately feared what they would later confirm: An unknown pathogen that has wiped out thousands of palms in Colombia since the 1950s was gaining a foothold in central Panama.

The disease, nicknamed Porroca (pore-OH-kuh), an indigenous word for "little leaf," had traveled in spurts west from Colombia. Until 1994, it had remained isolated in Panama's eastern, less-populated region. Its appearance near the canal was bad news, but government funding to tackle the problem kept falling through.

In 1996, Gilbert returned to the United States to take a faculty position at UC Berkeley, promptly securing a small grant so he could return to Panama to study Porroca. Gilbert enlisted the help of Ingrid Parker, a postdoctoral biologist doing work on the effects of nonindigenous organisms on native plants. What began as professional compatibility eventually grew; they married in 2001.

|

|

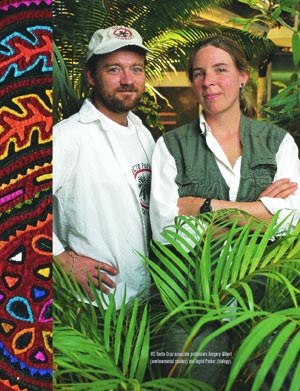

Gilbert and Parker, now associate professors of environmental studies and biology, respectively, at UCSC, first traveled to Panama together in 1998, when they began mapping each and every coconut palm in Kuna Yala. "We needed to know the baseline distribution of Porroca in the area," said Gilbert.

The infestation appeared to be in the early stages. They documented the "patchy" presence of Porroca in the Kuna Yala--some areas were devastated, but most were largely untouched--and they saw the need for a comprehensive evaluation of the region's coconut palms. Parker returned to California, while Gilbert stayed behind for a week of vacation that would prove fortuitous for everyone.

During his stayover, a former colleague asked Gilbert to give an impromptu lecture about Porroca to a group of ecotourists on a stopover in the Panama Canal. One visitor was so impressed by what she heard that she cornered Gilbert and asked for a funding proposal. She wanted to help him conduct the kind of long-term research that would "make a difference" (see "What a Difference One Donor Can Make," below).

Within weeks, she had provided $20,000 in funding with a promise of more to come, and Gilbert and Parker were back in business. During the following three years of intensive fieldwork, they mapped 200,000 trees, noting which were diseased and which appeared healthy. Early on, the hardest-hit areas were suffering from an infection rate of about 20 percent. By the next year, however, the infection rate in some locations was up to 50 percent. "It was massive," said Gilbert. "Many of the trees that had been infected the year before were now dead."

Porroca was on the run. Seeing its potential to destroy Panama's palms, Gilbert and Parker needed to act fast. They speculated that humans might be transmitting the disease, perhaps on machetes, and reached out to the Kuna, hoping to halt the disease and, in the process, help preserve a way of life.

Self-sufficient and wary of outsiders, the Kuna were initially skeptical of working with Gilbert and Parker. Culturally, the Kuna have a deep respect for the land. Community cooperatives clear small parcels along the coast to cultivate coconuts, bananas, plantains, fruit, and root crops like yucca, but old-growth forests still dominate the interior. In 1983, the Kuna set aside a 148,000-acre expanse of virgin rainforest along the southern border of their holdings as a territorial defense, becoming the first indigenous group in Latin America to establish, in effect, a nature reserve. The move attracted widespread support from international conservationists.

But it is largely the coconut palm that ensures the success of the Kuna's subsistence lifestyle. With a population of 32,000, the Kuna rely on coconuts as their top cash crop and only export. In 1990, they sold 5.4 million coconuts, largely to Colombia, where coconut oil is a key ingredient in soap and perfume. When the market for coconuts crashed in the early 1990s, exports plummeted to 3.2 million. The Kuna turned to commercial fishing to replace the lost income and have so far avoided the temptations of commercial forestry and mining.

But their commitment to conservation could be tested if economic pressures mount. "They have a great tradition of conservation, largely because they've had other sources of income," said Gilbert. "If they lose the production of coconuts because of disease, that could push them to do other things. They value their forest, but they can only afford to preserve it if they're able to survive by other means."

Gilbert and Parker approached the Kuna with respect, but they had a lot to learn about Kuna identity and traditions. Early on, for example, the pair discovered the value of meeting with the chiefs, or sahilas, of each island and explaining their work. This ritual entailed waiting in dark bamboo huts, drinking ceremonial drinks, and speaking through a translator. (Although most sahilas can speak Spanish, all official business takes place in the local Kuna language.) Sometimes they were met with suspicion. "The first year, it was touch and go with the Kuna," recalled Parker. "For a long time, we were 'those gringos with binoculars.' "

As Porroca spread, though, the Kuna became more receptive to working with Gilbert and Parker, whose generosity and appreciation of Kuna culture eventually helped them forge strong bonds. The second year went more smoothly, particularly after the pair made a presentation to the national Kuna Congress and received an official letter of permission from the three caciques, or head chiefs.

Embracing the research effort, the Kuna Congress tapped Edgardo Soo, a Kuna native, to serve as a guide for Gilbert and Parker. The congress lent the team their boat, and Soo promptly became a full-time employee, establishing an invaluable cultural and scientific link between the scientists and the Kuna. "When we met, Edgardo had never touched a computer, but within six months he was collecting data, entering it on a spreadsheet, and sending it to us on email," said Parker.

"It's been so exciting and interesting to get into the social aspects of the work," she added. "Living with the Kuna has given us a chance to see the world through an entirely different filter."

With Soo's help, the researchers launched an educational campaign, offering workshops and publishing brochures in Kuna and Spanish to help residents recognize symptoms of infection. The Kuna were encouraged not to move coconut plants or seeds, and Gilbert and Parker enlisted their help in reporting new areas of infestation.

Famous for their hand-stitched molas, the Kuna presented this expression of gratitude to Gilbert. Photo: Jim Mackenzie |

Throughout 1999, Porroca continued to spread, "jumping" to isolated mainland areas and traveling significant distances to four previously untouched islands. The disease was not behaving as predicted, and the baffled research team was forced to drop the human-transmission theory.

Working with the Kuna, the researchers ramped up their efforts and introduced control strategies, hoping that cutting down infected trees and smoking out insect carriers of Porroca would curb its spread. Implementing these measures proved to be fraught with cultural taboos: Six months into the experiments, Soo revealed to Gilbert and Parker that many Kuna were reluctant to cut down diseased palms because they believe coconuts are spiritual beings. It was a reminder of the value of interdisciplinary training for natural scientists, who typically lack the social science background that can enhance their fieldwork (see "New UCSC Research Center," below). Still, with Soo's help, the Kuna became so enthusiastic about participating in the experiments that the researchers had to turn people away.

Nevertheless, the team's efforts to control Porroca proved ineffective. By July 2000, the disease had "exploded," appearing on 53 islands two and three kilometers from the mainland. "It was a massive infestation and became a national issue for the Kuna," said Gilbert.

Tracking Porroca was proving frustrating, recalled Parker. "We were dealing with this mysterious disease, and nobody knew what organism caused it," she said. "We were trying to understand it by looking at the pattern of its effects, and it wasn't adding up."

That frustration, coupled with her intimate knowledge of the people who stood to suffer if she failed, posed a new challenge for Parker.

"I wasn't prepared for how much pressure there would be to work on a problem when somebody is waiting for the answer," said Parker. "It's so outside the realm of basic science. With this project, it has always been, 'We need to know yesterday.' "

Having ruled out all of the "easy answers," Gilbert and Parker turned to Nigel Harrison of the University of Florida's Research and Education Center in Fort Lauderdale. Harrison, the preeminent researcher on phytoplasma disease of palms, took up the challenge and spent nearly a year trying to identify the infectious bacteria that was wiping out the Kuna palms.

From preserved samples of the meristem, or growing part, of infected trees, Harrison was finally able to identify the offender, a previously unknown phytoplasma transmitted by a "piercing and sucking" insect probably smaller than a housefly.

Identifying the phytoplasma is an exciting breakthrough, but it begs the next question: Which insect actually carries the pathogen that causes Porroca? Gilbert estimates it could take a year to identify the disease-carrying pest by analyzing the DNA of phytoplasma inside the guts of thousands of possible vectors. If successful, that would open up a range of disease-control options, from trapping to selective pesticide use to using pheromones that interfere with insect reproduction.

Meanwhile, Gilbert and Parker are eager to turn their attention to analyzing the data they've compiled, having tracked the health of nearly 250,000 individual palm trees across hundreds of kilometers. With the "eyes and ears" of Kuna in the field, they will update their data every two years to construct the spatial analysis they hope will finally reveal what makes Porroca "explode" in some spots and fizzle in others.

That body of work is arguably the largest-ever epidemiological database of the spread of plant disease in the world. By comparison, ongoing monitoring of rust on North America's economically essential wheat crop lacks detail, and plant specialists studying sudden oak death in California can only dream of compiling such a thorough database, the value of which extends way beyond the Porroca infestation in Kuna Yala.

"It's pretty amazing," said Matteo Garbelotto, a forest pathologist and adjunct professor in UC Berkeley's Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management. "It's one of the best examples of the accumulation of scientific information about how plant disease spreads. It provides an invaluable baseline for sophisticated modeling that will help them discover meaningful variables, whatever they turn out to be--wind direction, temperature, rainfall, trading routes, or something else. Answers will come eventually."

Fortunately, their benefactor, who prefers to remain anonymous, is in for the long haul, having promised to fund the biannual trips that will enable Gilbert and Parker to see their project through to the end.

Gilbert and Parker have gotten another lucky break. Although they're not sure why, the Porroca epidemic seems to have stabilized. No major new infestations were identified in 2001, and a few sites actually disappeared due to the death or removal of diseased trees. "We saw a fair amount of recovery--10 to 20 percent of diseased trees had recovered," said Gilbert.

In the meantime, Gilbert and Parker sound at times almost apologetic about what they've accomplished. It's a ridiculous notion on many levels, not the least of which is that they've each pursued the Porroca project as a sideline to their primary research, squeezing in trips during quarter breaks and working without pay. Gilbert's primary research is on microbial ecology in tropical and temperate forest ecosystems, while Parker's current research focuses on pathogens among native and nonnative clovers on the California coast.

"We've gotten a really good start on this problem that deep down we always knew would be a long-term thing," said Parker. "But we all wish there'd been an easy answer."

New UCSC Research Center Factors Human Needs into Environmental Solutions

UCSC doctoral candidate in environmental studies Ernesto Mendez is working with peasant coffee farmers in El Salvador to promote sustainable agriculture in the region. Photo: Courtesy Ernesto Mendez |

The unparalleled pace of environmental degradation in the tropics cries out for intervention, and one of UCSC's newest research centers is helping transform the way universities and policy makers respond to the crisis.

The Center for Tropical Research in Ecology, Agriculture, and Development (CenTREAD) is preparing undergraduate and graduate students to integrate human needs into research that addresses complicated environmental problems in the tropics.

"As we learn about the ecological consequences of industrialization, resource consumption, and a booming population, we're seeing that solutions are inextricably linked to issues of social justice, economic development, and governance," said CenTREAD codirector Karen Holl, an associate professor of environmental studies at UCSC and coholder of the Pepper-Giberson Chair. "Solutions will require scientific training and research, but also an understanding of cultural, political, and economic systems."

In Panama, CenTREAD codirector Gregory Gilbert and biologist Ingrid Parker's ability to conduct scientific research could have been jeopardized if they weren't sensitive, adept, and dedicated enough to overcome problems posed by the unique challenges of working closely with the indigenous Kuna people. They experienced firsthand the need for environmental scientists to broaden their academic preparation.

Established in 2000, CenTREAD builds on the expertise of UCSC's faculty, whose commitment to interdisciplinary scholarship has attracted a "critical mass" of researchers and graduate students drawn to this new approach to ecological problem solving.

For doctoral candidates like Ernesto Mendez, whose dissertation in environmental studies focuses on ways to help peasant coffee farmers in El Salvador, CenTREAD represents a high-level endorsement of integrated research. "I've had professors almost apologize to me because they see what's involved," said Mendez. "But I feel lucky. We need to train people to do this, and I really appreciate the willingness and commitment of faculty to put themselves out there for us."

Mendez, whose father and grandfather farmed in El Salvador, is at the forefront of efforts to bring Earth-friendly farming to the tropics. For more than five years, he has shared his expertise in agroforestry and resource management with small-scale coffee farmers struggling to survive an international crash in coffee prices. Many are eager to diversify their plantations, but they lack the scientific knowledge to make changes, and they're unaware of niche marketing opportunities like those created by the shade-grown coffee movement.

Blending the science of sustainable agriculture with an understanding of social needs is at the heart of Mendez's research--and at the heart of international efforts to protect what's left of tropical ecosystems. For example, Mendez's research has revealed a weakness in the shade-grown coffee certification program, which has created consumer demand for coffee grown on land that maintains certain levels of native tree biodiversity. Many small-scale coffee farmers are hesitant to participate because their livelihood depends on being able to harvest small amounts of timber for firewood and lumber, yet these growers represent "huge conservation potential" because nearly 80 percent of coffee in El Salvador is grown by small operators, according to Mendez.

"What we need is a compromise that would include more farmers, so they can participate in conservation efforts and take advantage of new marketing opportunities," said Mendez. "We have to compromise so farmers will also benefit. It's not just about saving trees."

Researchers working throughout the developing world are recognizing the need to incorporate broader knowledge of region-specific needs into their strategies to protect the environment. CenTREAD is offering specialists like Mendez, whose background includes a bachelor's degree in agronomy and a master's in agroforestry, training that encompasses fields like rural development sociology, political economy, and anthropology. The codirectors of CenTREAD are raising funds to support students from the tropics who want to come to UCSC, and to build a visiting scholars program to increase interaction and research collaborations between UCSC researchers and their counterparts in Latin America.

For more information, visit centread.ucsc.edu.

-Jennifer McNulty

What a Difference One Donor Can Make

Jane Carver* managed money for the federal government for 35 years, so she knows about red tape--and how to cut through it. That's precisely what she has done for UCSC researchers Gregory Gilbert and Ingrid Parker, who've been on the trail of Porroca, the puzzling disease that's killing coconut palms in Panama.

Since 1998, Carver has given more than $65,000 in no-strings-attached support to Gilbert and Parker's work. She first learned about Porroca as an ecotourist in Panama in 1998, when Gilbert gave a presentation to her travel group about the spread of the disease onto Kuna Indian land and the threat it posed to a proud people who depend on coconuts for food and income.

"When I heard him, I just thought 'Here's a fellow doing absolutely wonderful things, and he has to jump through all sorts of hoops to get the money he needs to do his work. That's awful,' " recalled Carver. "I worked for the government. I know about rules and regulations. They measure everything, and they send people to inspect you who know less than you do."

Carver decided then and there to help fund Gilbert and Parker's research. She asked Gilbert for an outline of what was needed, and within weeks she put a check in the mail. No fuss, no muss.

"I've always been more interested in what's outdoors than what's indoors," said Carver, speaking appreciatively of the beauty of the woods around her Boston-area home, a region that was completely deforested during the 17th and 18th centuries. "It seems that for anyone who does any reading, you'd want to do as much for sustainability as you can."

Carver's help has literally kept the Porroca project alive. Unbeknownst to Carver until recently, Gilbert and Parker have donated their time to make her money go as far as possible. "You cannot imagine how productive the two of them are," said Carver. "They get the maximum amount of work done for the absolute minimum amount of money."

For the researchers, Carver is a dream come true. She has complete confidence in their abilities and their judgment, she doesn't stipulate how the funds are to be spent, and she is committed to the project for the long haul.

"You can always find the money for one trip," said Gilbert. "What we needed when we met her was long-term support."

Carver, who has also traveled to Guatemala and Belize, calls the Kuna "wary of Westerners." She credits Gilbert and Parker with being "wonderful ambassadors for the Western world."

Carver herself is quite content to let Gilbert and Parker do the fieldwork. Having accompanied them on one trip, she said that was enough.

"You cannot imagine the heat, under the blazing sun in boots, pants, a long-sleeved shirt, and hat, with scissor grass up to your nose," she recalled, laughing at the memory of her misery. "Greg and Ingrid thought it was wonderful, and I thought I was going to die!"

Carver recently gave an additional $20,000 to UCSC's CenTREAD project to support students doing conservation and agroecological research in the tropics (see "New UCSC Research Center," above). "When I look at the cost of taking a trip, I think my money might be better spent elsewhere, like on CenTREAD," she said.

Carver's story of generosity shows what a difference one person can make. "She doesn't see herself as a philanthropist," said Gilbert. "She just wanted to make a difference."

* Jane Carver is not her real name; the donor prefers to remain anonymous.

-Jennifer McNulty