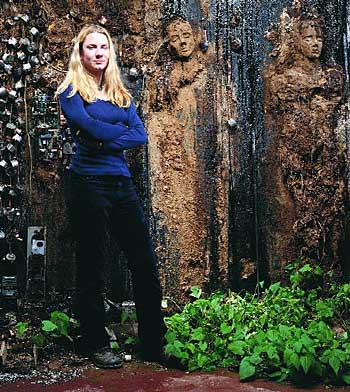

is the mouse mightier than the pen?Artistic Expression"We've always regarded art as this incredibly deep and profound expression of humanity. The fact that computer-generated art can be so moving disturbs a lot of people. It challenges our fundamental belief of art as a sacrosanct human activity."–David CopeArtist Anna Sprent with her installation, Test (Photo: R. R. Jones)  Sprent, a member of UCSC's class of 2000, has grown up in a world where chess programs outwit chess champions, lovers meet inside electronic chat rooms, and geneticists decipher DNA to clone living creatures. As computers have become more powerful and applications more sophisticated, their very existence is challenging humanity's fundamental understanding of itself in a way that hasn't happened since Darwin drew a new family tree for the human species. In the art world, the new technology has sparked passionate debate over the dilemma that Sprent and other artists must confront on a regular basis these days: What is the role of the computer in artistic expression? The most frequently voiced concern is that computers are elbowing in on the actual act of creation. That charge is often directed at composer and UCSC music professor David Cope, the inventor of Experiments in Musical Intelligence ("Emmy"), a computer program that creates original music in the style of other composers. Emmy's compositions have been released on three CDs (on the Centaur label) and performed around the world. Cope says that the myriad objections he hears from critics of programs such as Emmy and Aaron (a robot that paints original art) boil down to one word: intent. "No matter what critics tell me, the subtext is the same. Emmy can create beautiful things, but it doesn't intend for them to be beautiful. Therefore, many feel that they're not to be taken as seriously as human creations, which have intent. "We've always regarded art as this incredibly deep and profound expression of humanity," he says. "The fact that computer-generated art can be so moving disturbs a lot of people. It challenges our fundamental belief of art as a sacrosanct human activity. It challenges our definition of what it means to be human." Even as debate rages about the role computers should play in the process of creation, new and extraordinary examples of computer-assisted art continue to surface--in arenas ranging from home studios to metropolitan museums and community stages to the big screen. At UCSC, high-end computer labs and technology turn the phenomenal into the achievable: A film and digital media professor produces a clip of himself in a snowstorm--one that he shot in the heat of the summer. A theater arts staff technician uses digital-mixing software and hardware to create the screech and clang of a car crash, an effect that is so realistic it makes audiences jump in momentary panic. Art students mount a gallery show in which motion sensors activate various film clips; the images change in response to the movements of the viewer, creating a kind of interactive dance. As these kinds of computer-assisted creations proliferate, the sometimes rocky marriage of art and technology will only demand greater scrutiny, especially by the newest generation of artists--among them Anna Sprent. Although she rarely pushes the "on" key to a computer herself, Sprent isn't bothered by artists who do. "There's nothing wrong with bringing computers into the creative process," she says. "I've seen fantastic high-tech pieces, and I've seen ineffective ones. Ultimately, what matters is that the artist is passionate about what he or she is doing." --Barbara McKenna |

Return to Winter 2000 Issue Contents | Millennium Feature