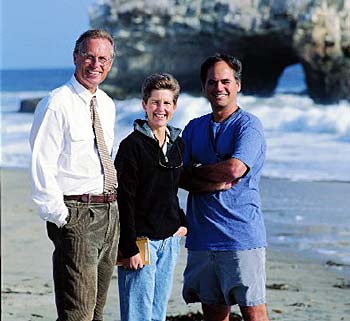

integrating science and policyEnvironment"The goal of our research is to be more inclusive--to understand not only ocean systems but also our role in protecting them."–Gary GriggsIMS director Gary Griggs, fisheries

sociologist Carrie

On the California coast near San Diego, large intake pipes suck vast amounts of seawater into the San Onofre nuclear power plant each day. The water provides vital cooling for the plant, but huge numbers of larval fish are sacrificed in the process. Enter UC Santa Cruz biologist Peter Raimondi. A member of the scientific advisory panel of the California Coastal Commission, Raimondi helped evaluate environmental damage caused by the plant. Thanks in part to his work, a wetland will be restored and the largest artificial kelp reef ever built for biological restoration is being constructed about 15 miles north of San Onofre. These sites will provide life-sustaining habitat for fish, eggs, and larvae to help replace those that are being lost. "It won't restore the fish in the immediate vicinity of the plant," says Raimondi, an associate professor of biology. "But it will help make up for some of the loss." Problem solving. It is becoming an ever larger portion of the work being done by UCSC's marine scientists. Many, including Raimondi, feel compelled to "give back" to society by sharing their expertise with government agencies, policy-making boards, environmental organizations, and nonprofit groups. This applied work is in keeping with the vision of Gary Griggs, director of UCSC's Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS). "The goal of our research is to be more inclusive--to understand not only ocean systems but also our role in protecting them," says Griggs. Indeed, Griggs's leadership reflects the growing integration of scientific research and policy making that is taking place as both sides attempt to span a gap that has at times had devastating environmental consequences. A generation ago, for example, abalone were plentiful in California, but insufficient oversight allowed unregulated harvests of the seafood delicacy, and the abalone population crashed. By the time limits were put in place, regulators had no choice but to ban all commercial harvesting. Such mistakes are clearly avoidable, and Griggs has spent years shoring up relationships to facilitate better communication. During his tenure, he has established partnerships with numerous state and federal agencies, including the National Marine Fisheries Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the California Department of Fish and Game. Those collaborations offer researchers the benefits of working across institutional boundaries, and they give UCSC scientists a direct link to the people who make the policies they hope to influence. Marc Mangel, a professor of environmental studies who specializes in population biology, has witnessed a shift over the years in the way that fishery regulations are interpreted. Until recently, Congress pushed for the "maximum yield," encouraging the fishing industry to harvest the highest yields possible. Recently, however, the focus has shifted toward sustainability, a trickier concept that seeks to balance human demands with harvests that will preserve fish populations and maintain biological diversity. It's a change Mangel attributes to greater environmental awareness generally and also to increased interaction between scientists and policy makers. Mangel sums up the belief of many when he says, "Scientists shouldn't make policy, but they should frame the context in which policy discussions take place." For Carrie Pomeroy, that has meant broadening the horizons of marine science research. A fisheries sociologist, she stresses the need to understand more than just biology when drafting marine resource regulations. "Policy makers are responsible for protecting ocean resources, but to be able to make effective policy, we need to understand the way people affect--and are affected by--those resources and their management," says Pomeroy, an IMS assistant research scientist. Pomeroy works hard to maintain the trust of the fishing industry as she explores questions like whether fishermen congregate on the edges of marine reserves, where logic suggests fish populations might be higher. "While perfectly legal, and actually pretty smart, that activity could have unintended consequences, which is why it's so critical to study how people interact with the marine environment," says Pomeroy. "There's a growing recognition that the people element is relevant to resource management." By training the next generation of marine biologists, IMS scientists like Pomeroy are making a lasting contribution to the union of science and policy. Through their work, IMS researchers are serving as role models for students, many of whom have a growing interest in work that has applied significance. "I feel that I have a social responsibility to do this kind of work," says assistant professor of biology Mark Carr, who serves on a panel that is helping design a marine reserve in the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California. "It's really pretty simple: Are we going to start making decisions based on scientific knowledge, or not? In the end, politics may override science. But I have to try." --Jennifer McNulty |