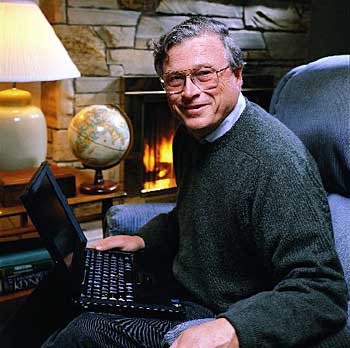

balancing opportunity and accountabilityGlobal Economics"Countries that previously had no access to international financial markets now have access to capital they've never had, and they also have access to trouble they've never had."–Michael DooleyEconomist Michael Dooley

(Photo: R. R. Jones)  For UCSC economics professor Michael Dooley, however, the picture is in sharp focus. Before coming to UCSC in 1992, Dooley spent more than 20 years studying and dealing with financial crises, first at the Federal Reserve in Washington, D.C., and then as an assistant director of the research department of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), where he remains a consultant. Since then, he has advised the governments of numerous developing countries as they strive to become the world's newest economic players. Reflecting on the past decade, Dooley observes that economic globalization has ushered in an era of unparalleled opportunity--and uncertainty. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, developing countries in Latin America, Asia, Eastern Europe, and the former Soviet Union are relying on newly emergent market-oriented economies, rather than the government, to distribute goods, services, and credit. Governments are selling off some industries, privatizing others, and deregulating fields like finance, telecommunications, and mining. Like dropping a large boulder into a small pond, this change has generated tsunami-sized effects that have washed over the world's financial markets, says Dooley. "Countries that previously had no access to international financial markets now have access to capital they've never had," he says, "and they also have access to trouble they've never had." The recent Asian economic crisis, and the Mexican economic crisis of 1994, can be traced quite directly to this liberalization of capital markets. The current challenge, according to Dooley, is figuring out how to preserve new markets while avoiding the destabilizing financial crises that have occurred with increasing frequency and magnitude. "That's a very big question," says Dooley, acknowledging that there are no ready answers. One major problem is that developing countries lack the regulatory structures and the expertise within their domestic banks to operate in an open economic system. By contrast, industrialized countries have a lot more experience, and they regulate their financial markets pretty heavily. There's a simple and compelling reason for the high level of oversight: Governments want to do everything they can to avoid having to rescue banks. "All governments are implicitly liable for their banking systems," says Dooley. "You just don't let your banks go, because if you do, all hell breaks loose." In the U.S., the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation regulate the activities of the nation's banks. In developing countries, the absence of such a system, coupled with corruption and high levels of risktaking, has left many governments unable to cope with the consequences, as recent history has shown. Unlike the "old days," when government overspending was the culprit, countries today are getting into trouble when their banks make bad loans. Forced to take over massive debts, governments have no alternative but to turn to the IMF for help. The IMF operates like a financial safety net. An international membership organization made up of 182 countries, the IMF lends money to members that are in financial trouble on the condition that they undertake specific economic reforms stipulated by member governments. "Countries turn to the IMF when they can't borrow from anybody else," says Dooley. "They're already on life support. The patient is in critical condition." The IMF has, however, pulled the plug on Russia, where millions of aid dollars have vanished into the pockets of corrupt officials. Until Russia restructures its financial system, it will get no more assistance, says Dooley. What remains to be seen, however, is whether the recent series of high-profile "bailouts" that began with Mexico in 1994 has sent an irreversible signal to developing nations that it's okay to take excessive risks because the international community will always be there to patch things up. "There's no question that the market's perception of risk after Mexico changed dramatically," says Dooley. "But there's also a growing recognition that governments have to monitor and somehow enforce limits on what people are doing with their money. If you're a government, you've got to get a hold on that. You've got to protect yourself." Creating incentives for governments to exert some control is clearly the next step, says Dooley. The IMF, along with the World Bank and the regional development banks, is making a big push to help developing countries restructure their banking systems. They need look no further than the U.S. for a good model, says Dooley. "You need the rule of law for open financial markets to work," he says with finality. But then, with a wry smile, he hastens to add: "Of course, our system didn't evolve overnight. We had our share of robber barons, too. We had a pretty rapacious system for a very long time." --Jennifer McNulty |