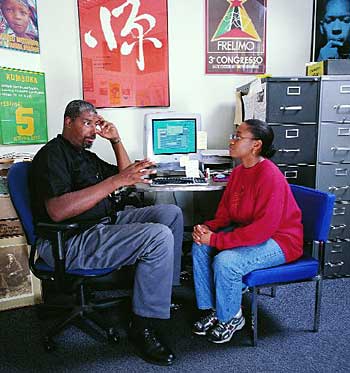

seeking social justiceRace Relations"Here we are at the dawn of the next millennium and still–with all the history we have to learn from, with all the struggles we've been through–people get pulled over, beaten, and even starve to death, just because of the color of their skin."–David AnthonyOakes College provost David Anthony counsels student Arinn Filer (Photo: R. R. Jones)  Poverty levels for minority children in the U.S. have risen over the last several decades; incarceration rates continue to be disproportionately high for some minority groups as well; hate crimes occur in the U.S. and abroad with alarming regularity; and debt to former colonial powers is causing devastating poverty in many Third World countries. "Most people have no idea of the forces arrayed against whole sectors of society," says David Anthony, an associate professor of history. "The race you are born into clearly affects the trajectory of your life." A specialist in African and African American history, Anthony has spent a lifetime teaching, researching, writing about, and living with racism. He can easily explain the parallels between the postCivil War Reconstruction Era and the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. He can describe the link between cutbacks in social services and the rise in crime in communities from Compton to Somalia. And he can illustrate the connection between the end of the Cold War in 1989 and the current economic and social upheaval in Africa. But, despite his expertise, there is one question on racism that perpetually stumps Anthony: "How do I explain it to my kids?" "Here we are at the dawn of the next millennium and still--with all the history we have to learn from, with all the struggles we've been through--people get pulled over, beaten, and even starve to death, just because of the color of their skin." There is, of course, no satisfying answer to his question. That is why, as both an educator and civil rights activist, Anthony is interested not only in understanding the forces of racism, but in addressing them. His conviction led him to a career in teaching, and it was also behind his decision, in 1995, to accept the position of provost of UCSC's Oakes College. "I went into this business to open doors. Whether it's teaching a roomful of students or speaking with a troubled individual in my office or finding the funds for diversity programming, education is a powerful way to address social ills, to create social justice," he says. Anthony had mixed feelings about taking on the administrative post at Oakes. It meant cutting back on his teaching and his research project--a biography on African American Max Yergan, a Christian missionary and leader in communist and African American movements who later became an archconservative activist. But becoming provost also meant Anthony could help students in new ways: as an adviser, as someone who can fund a project, or as a guide through the sometimes complex landscape of academia. "There's a saying: If you don't know where you're going, any road will take you," he says. "As teachers and administrators, we always hope that we're helping students find direction." They don't give Oscars for powerful teaching, or shares of stock for graduating one's students. For Anthony, the rewards of the job come from engaging in his dual passions of teaching and working for social justice. "It's encouraging to see, especially at Oakes, how many students who 'make it' after graduation are involved in the process of effecting social change," he says. As a historian, with the perspective of centuries in mind, Anthony knows that creating a more egalitarian world can't be accomplished in a single lifetime. But it hasn't stopped him from trying. --Barbara McKenna |