Time and the RIVER

Photo: Oeffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Kunstmuseum,

Martin Bühler

Tucked into a redwood forest in the Santa Cruz Mountains sits a little slice of Germany, a Tyrolean-style restaurant. One winter evening a guest asked if the dinner special, salmon with dill sauce, was an authentic German recipe.

"No, it can't be," the waitress replied. "There are no salmon in Germany." But the guest persisted. Perhaps it was an old recipe, he wondered, because there had been salmon in the Rhine, western Europe's major waterway and the only river connecting the Swiss Alps to the North Sea.

In fact, annual salmon catches in the Rhine once ran at more than half a million, and German cookbooks featured plenty of salmon recipes. How could the waitress think there were no salmon in Germany? Because by 1950, well before the young woman was born, salmon had completely disappeared from the river.

Why the salmon vanished--and whether they can be reestablished--is part of a chilling environmental tale told by UCSC history professor Mark Cioc in his new book, The Rhine. Covering nearly 200 years of the river's recent history, Cioc's book describes a river sacrificed to economic progress, a story sadly familiar in industrialized nations. The book also describes more recent attempts by Rhine nations to reverse the devastating damage.

"Every country seems to insist on its sovereign right to go through the same problems with the environment, instead of learning from the experiences of other countries," says Cioc. "For a period of time as nations industrialize, they feel they have the freedom to do what they want to the water and air. First they pollute with impunity, and then later they try to clean up."

'Improving' the Rhine: These maps illustrate the dramatic physical transformation of the Rhine River and its floodplain resulting from urbanization of the river over the 135-year period stretching from 1828 (top) to 1872 (center) to 1963 (bottom). Photo: Courtesy Mark Cioc |

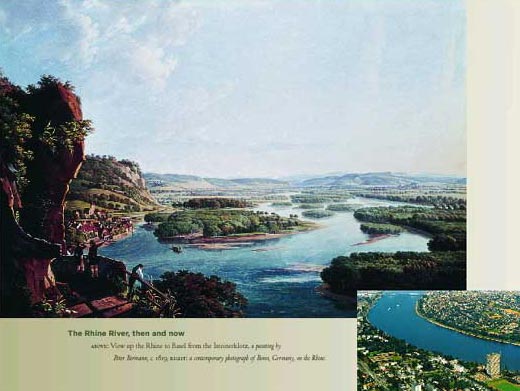

Cioc's tale begins with the 19th-century "Romantic Rhine," when a rich biodiversity extended from riverbed to floodplain's edge, and progresses to the Rhine's 20th-century incarnation as "Europe's romantic sewer."

By then, the river had been transformed into a virtual canal, its bed straightened and lined with cement, its banks overdeveloped with factories and cities, its biodiversity shattered, and its channel so polluted that the liquid it carried could barely be called water.

"I spent about three years of my education living on the Rhine and ignoring it," says Cioc, who was a Fulbright Scholar at Mainz University in the 1970s. Years later, he discovered poignant hints of the Romantic Rhine along some river stretches, especially in places where centuries-old boat towpaths have been converted into bicycle trails. In the early 1990s, Cioc was cycling on a former towpath along the Rhine when the idea for his book came to him. "These bike paths are quite close to the river, and that makes them ideal for observing what has happened to the Rhine over the past two centuries," says Cioc.

The Rhine springs up in the Swiss Alps and flows north across Europe, through Switzerland, Germany, and France to the Netherlands, where it forms a massive delta at the port of Rotterdam. It carries more commercial traffic than any other European river, generates power, and is used for industry, agriculture, and sanitation, with almost 50 million people living in its watershed. The Rhine has served humans well, and this utility has nearly been the death of it.

In the early 19th century, as the river's beauty was being revered by poets, writers, artists, and tourists, governments along the Rhine were looking beyond the river's scenic qualities. Even then, the importance of the river to European commerce was so obvious that in 1815 the nations along the Rhine created the Rhine Commission, declaring the river a shared commercial waterway and its banks free-trade zones.

With the exception of several years during the Nazi era, the commission has met annually since 1831. It has survived wars, revolutions, state unifications, and changes in national boundaries. Establishment of the Rhine Commission marked what Cioc calls "the first step in the long march of diplomacy that culminated in the Common Market and the European Union." But it also set the stage for the near destruction of the river's viability to sustain both life and commerce.

Cioc meticulously chronicles how many of the riparian engineering projects done under the aegis of the Rhine Commission, each with a goal of "improving" the river for human use, often achieved the opposite effect. These projects, done in the name of better navigation and less flooding, produced more flooding, along with a loss of biodiversity and overdevelopment along the river and its floodplain.

There was no single engineering project to blame, but rather the incremental legacy of many projects over many years. "You think if you build this dam, or block that tributary, it's not going to make a difference," Cioc says. "But then you do another and another and another, and suddenly, the river's viability is gone. And it goes fast."

First came a flood-control project on the Upper Rhine, a portion of the river extending north from the Swiss-German border into southern Germany. Beginning in 1817 and continuing for nearly 60 years, this stretch of river channel was straightened--its meandering loops, crisscrossing multiple channels, and oxbows eliminated. The plan also had the desired effect of improving navigation and increasing arable land in the river basin.

Subsequent engineering projects attempted to further improve navigation in the Middle and Lower Rhine, which extends through Germany to the Dutch border. Reefs were blasted out, banks were reshaped by dredging, and the new shore was reinforced with cement. The Dutch dredged, built dams, and cut channels, consolidating water from the delta's lattice of creeks so effectively that Rotterdam became the world's largest harbor.

Meanwhile, the industrial revolution was moving into high gear. Coal mining and iron and steel manufacturing changed much of the watershed land from agricultural to industrial use, polluting the river's water and watershed. River cities had been using the Rhine for sewage disposal for centuries, but increased populations meant increased sewage. Chemical plants and chemical-based industries started competing for space on the riverbanks, using the Rhine water for manufacturing and dumping.

Hydroelectric dam construction began in the late 19th century, destroying riparian habitats and trapping polluted water. Oil refineries and nuclear power plants joined the detrimental lineup in the 20th century, raising the water temperature by sending heated wastewater back into the Rhine.

When an organized effort to repair the river finally began in 1950, the impetus was not the environmental movement, nor did it happen because someone noticed that the salmon had vanished. It happened because the Rhine governments realized that people, property, and the economy along the river were endangered.

Pollution of industrial and urban water supplies in the delta had become so bad it could no longer be ignored, and the Dutch government took the lead in creating the Rhine Protection Commission. Focused on assessing water quality in the river, this commission became the first in a series of government organizations established during the ongoing restoration efforts.

|

|

When multiple "100-year" floods occurred in quick succession, the governments also began an effort to restore some of the floodplains destroyed a hundred years earlier. "The notion that you can domesticate a river and it's over and done with is absurd," says Cioc.

Cleanup efforts were accelerated by the catastrophic 1986 fire in a storage facility at the Swiss Sandoz agrochemical plant. Since the building lacked a sprinkler system, firefighters doused the blaze with firehoses, sending 10 to 30 metric tons of raw chemicals into the Rhine. As the world watched, the chemicals washed down the river to the North Sea, wiping out virtually all fish and plant life along the way. The Sandoz accident raised international awareness of environmental problems in the Rhine, and coincided with the Rhine nations' cleanup discussions and the rise in popularity of the German Green Party, a political organization which has as its core platform the protection of the environment. "All these factors combined to put more and more focus on preserving the biology of the river," says Cioc.

Today, the Rhine nations have established mechanisms to monitor, protect, and rehabilitate the river, and the Rhine is slowly recovering its water quality, a measure of its biodiversity, and some floodplains. The Rhine nations have even initiated projects designed to bring salmon back to the river.

Spawning grounds and nursing areas are being restored. To circumvent dams and weirs blocking migration routes, fish ladders and passages are being built. But previous destruction of salmon habitat was so thorough that the current restoration has only laid the groundwork for a possible, and very gradual, return of the great fish to the Rhine.

Cioc, who calls salmon the "embodiment of the river's soul and the foodstuff of myth and legend," predicts that one day there will even be a self-sustaining salmon population, although only at a small fraction of the spectacular runs of the past.

"I thought when I was doing research for this book that it would be a story of decline and rebirth, but it's really not," says Cioc. "After a river has been manipulated to this extent, there's a permanence to the damage."

Cioc also sees one other obstacle to the river's full restoration: The Rhine's biology will remain secondary to the Rhine's economy. "The river will continue to improve," says Cioc, "but only as long as the improvements serve human populations who live and work along the Rhine."

-Ann M. Gibb