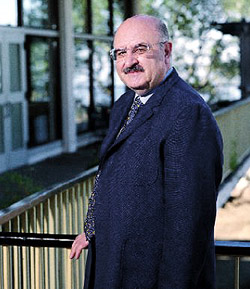

Champion of the Humanities

A conversation with UCSC's new dean

An internationally respected professor of English and comparative literature, Wlad Godzich

came to UCSC from the University of Geneva in Switzerland. He is the author of several

critically acclaimed books on literature and

language, including The Culture of Literacy.

Photo R. R. Jones

An internationally respected professor of English and comparative literature, Wlad Godzich

came to UCSC from the University of Geneva in Switzerland. He is the author of several

critically acclaimed books on literature and

language, including The Culture of Literacy.

Photo R. R. Jones

Wlad Godzich, completing his first year as dean of UCSC's Division of Humanities, is naturally curious--about any number of subjects. Once a decade, for example, he takes a university-level course in human anatomy because "humanists can't comment on the ethics of modern medicine if they don't truly understand the latest developments in the field." He is at his most passionate, however, discussing the state of humanities scholarship in higher education.

In the interview that follows, he describes the political and economic forces that have reduced humanities offerings on U.S. campuses. And he makes the case for reversing that trend, arguing that literary scholars, historians, philosophers, and other humanists offer perspectives that can help society confront some of its most daunting challenges. --Jim Burns

Do you accept the view that humanities in American higher education is in a state of crisis?

Yes. If we go back to, say, the late 1950s, humanities represented 40 percent of the classroom enrollments on most campuses. If we jump forward to the mid-1990s, we see that the humanities represent on most campuses only about 20 percent of enrollments. So this is a very, very drastic diminution over time.

In addition, the current humanities enrollments, in large measure, consist of the important innovations that were born in the 1960s and '70s--ethnic-study programs, women's studies, new departments of an interdisciplinary nature. These programs were not part of the American university in the 1950s. So once you factor that in, all that is left of what was the humanities in the late 1950s is roughly about 10 percent of the classroom enrollments on most campuses. This is a very dramatic change.

How would you explain this decline?

The humanities were central in the creation of universities in the United States, and humanities departments were the first that most universities had, especially the oldest ones on the East Coast. It was in American universities that you had a sequence of courses in Western civilization that were developed in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s. These courses were interdisciplinary in orientation, and they prepared students for the specialization of their last two years, where they would perhaps go on to earn a prelaw or a premed degree to prepare them both for academic and professional life.

In those days, university administrators also maintained a ratio of four humanities faculty to one natural sciences faculty for a less lofty reason: It was more expensive to train a natural scientist. For a scientist, you have to have labs, you have to have equipment that becomes obsolete. The equipment of a humanist is cumulative. You buy a book and 500 years later, if you have handled it properly, you can still use it.

Things began to change under the impetus of the Cold War and especially with the Sputnik launch in 1957. The federal government began to be very involved in higher education. It began to provide funds for research, primarily in the sciences. The gap began to grow, then, between the funding that was received for the sciences and that which was received for the humanities.

The turbulence of the 1960s also contributed to a decline of the humanities. Humanists were embracing concepts that were extremely controversial at that time, having to do with racial equality, pacifism, women's rights, the attitude toward work, the future of the family, the environment, you name it, it was all suddenly thrust in the forefront. Very often it was humanists who were carrying the banner. That made administrators, who supported these humanists, very nervous. The administrators were criticized by legislators, by public officials, by their own boards of trustees, or they were simply punished by having their budgets cut.

The economic recession of the 1970s also played a role in reducing humanities offerings in higher education. The period of high inflation that concluded that decade pushed many students--and even more university administrators--toward what became known as the "New Vocationalism," a utilitarian conception of the university as a production site for workers rather than a place where people learn.

So you began to have a policy of benign neglect applied to the humanities. Essentially humanities budgets began to be frozen, and they remained pretty much frozen all the way into the '80s. This was of course a period when American universities were growing, so, as the humanities budgets remained constant, the growth was transferred to other divisions within the university.

What are the ramifications of this reduced support?

The downside is the loss to the society at large, especially now, when there is such major turbulence in the area of values. We need to adapt to the transformations brought upon us by technology, globalization, the breaking up of the traditional family.

Bear in mind that until 1950 or so no one even knew that there was such a human being as a teenager. This is an invention of the past 40 or 50 years. This is something that would have come as a total surprise to a Victorian, for example, that you could have some new human being called a teenager, wielding increasingly important economic and political power--becoming an arbiter of cultural trends. So that popular music, rock and roll, certain kinds of movies, are geared toward that population.

These are just a few of the issues, the transformations, that would benefit greatly from the input of humanists.

How can humanists help us consider such transformations?

Let's ask ourselves a very simple question: What are the humanities about? The humanities are fundamentally about what makes us human. It's not that our essence has been fixed once and for all. The history of humankind is our constant revision, refinement, and redetermination of what it means to be human.

We know that until 100 to 150 years ago, it was still heretical for many people to consider that women were human beings, endowed with reason. That's why they didn't have legal rights. It's only slowly that they have acquired those rights, in some countries they still don't have those rights, and certain countries are retreating from this, such as Afghanistan at the present moment. But humanists have made women's rights a part of their agenda.

Today, who are we allowing to define the essence of humanity? Biologists, who tell us that if we let them they will clone human beings and engage in the industrial production of human beings? Or economists, who tell us that they know what motivates us, that they know what dictates and controls our behavior?

Matters like these need interpretation, they need to be placed in historical context, they need to be understood.

What first impressions have you formed about UCSC's ability to participate in this sort of inquiry?

Well, it's important to note that UCSC, as a campus, was born and has developed precisely during this period of turmoil nationally for humanities. And, the retirement in recent years of many of our division's founding faculty has further affected the quality and quantity of humanities offerings at UCSC.

It is our division's goal to arrest this decline, refocus the work of the division, and recapture the campuswide role that humanities scholarship should play in this new century.

I am, therefore, very pleased to have so many remarkable individuals in a number of departments already addressing some of society's most important issues.

The History of Conscious-ness Department, for example, deals with the kind of cultural, historical, and political issues--in an interdisplinary way-- that cannot be dealt with elsewhere in academia. And the Women's Studies Department on this campus is quite a remarkable endeavor, which combines very rigorous intellectual training with social activism. The internships that the students in women's studies conduct are the vital line for so many of the community organizations in this county and in the surrounding region.

In fact, we have, in all of our humanities departments, a kind of a interdisciplinary spirit, a willingness to engage across boundaries here, and a desire to ask the kinds of questions it would be difficult to ask in other places.

It's very, very difficult on a larger campus--let's say Berkeley for example--to come up with a new program. When you talk to deans or to higher administrators there, they speak of their frustration at being able to get something past the faculty. Here, there is much greater willingness to try things out; people are much more open. This is another reason I think that one can be optimistic about the future of humanities at UCSC.

In your time here, are there particular research activities that have caught your eye?

We have a whole range of fascinating work that is being done in the History Department. We have research on what I would call, broadly, the democratization process around the world. We have a number of historians who are interested in understanding how processes of inclusion--of including different strata of society, different age groups, gender groups--have evolved. For example, one of our historians, Gail Hershatter, works a great deal in China, trying to understand how the Cultural Revolution affected women, how these women now understand their position in relation to this very large culture, and how that transformation has helped control the population growth in China and is leading to a different kind of Chinese society.

Mark Cioc in the History Department has just finished a book on the history of the Rhine River. This is the first significant work on the environmental history of a European river to be written by an American. This river is particularly important to European history because it crosses a number of countries and has been a very significant boundary. Its history is not just natural history, but it is the history of the dams and the bridges and of fights and competing interests.

UCSC has many other exceptional humanists. People like Helene Moglen in the Literature Department, who has just published a book on the origins of the novel. The standard theory of the origin of the novel is that it was linked to the rise of the bourgeoisie and required a certain kind of realism. You had to actually describe lives as they were led. She looks at the early history of the novel and shows that there's actually a tension between this realistic element and an element of fantasy.

Or like Chris Connery in literature, who is writing a history of the Pacific Ocean: What have people thought of the Pacific, how have they imagined it, and how have those thoughts changed over time?

How do you see UCSC's new Institute for Humanities Research evolving?

The institute was created in 1999 to support humanities faculty and graduate student research. It is also the home of the Center for Cultural Studies, one of the nation's premier centers of interdisciplinary research, and a number of other focused research activities.

The institute is a very important part of the future of the humanities on this campus, and we hope it will have broader influence as well. It is already becoming a place where research agendas for the future are being identified. One of the major responsibilities of this institute is to ensure that we simply don't fall back into the tried and the true, but identify new domains in which humanists ought to begin to work.

Let me give you an example of this kind of inquiry. We are beginning to examine how the domination of images over written language is determining the nature of our experience. What kinds of values are linked to this change?

Compare what's happening today to the changes brought about by the introduction of the textbook. Before you had textbooks you had to learn from one master. The textbook, on the other hand, was the distillation of the knowledge of several masters. But in order to learn from several masters, readers of those early textbooks had to accept the notion that they could learn from somebody whom they had never met. So, textbooks not only made knowledge available to more people, their very acceptance as a souce of knowledge promoted a certain amount of equality between human beings.

In fact, the people who invented textbooks--the Dutch in the 16th century--didn't think that this would lead to democracy. But 60 to 70 years later, they realized that this print culture contained within it a seed of human equality-- and that literacy was a way of enforcing equality.

So, how is today's digital culture, in which images dominate printed language, changing human values? How is the Internet, which is making available an abundance of information, transforming us? We need to ask ourselves these kinds of questions. And who is going to ask these questions if not humanists?

Return to Summer 2001 Issue Contents